The work on the digital editions of Muḥammad Kurd ʿAlī’s journal al-Muqtabas (Damascus and Cairo, 1906–18) and ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Iskandarānī’s journal al-Ḥaqāʾiq (Damascus, 1910–12) continued within the framework of OpenArabicPE. Contributions from our interns Manzi Tanna-Händel, Xaver Kretzschmar, Klara Mayer, Tobias Sick and Hans Magne Jaatun allowed us to release a further four volumes. Readers can find a project description in the last annual report and I will focus here on the first foray into the analysis of our corpus. One of the driving research questions behind OpenArabicPE focusses on reconstructing the ideosphere of the late Ottoman and early Arabic press through establishing networks of authors and texts published and referenced in the periodicals. With regards to al-Muqtabas and al-Ḥaqāʾiq, we ask: who published what in late Ottoman Damascus? As well as, what was read in late Ottoman Damascus?

Any sort of meaningful computational analysis of the global connections between authors, texts, and periodicals as a venue for publication and review requires access to reliable standardised bibliographic metadata as a bare minimum. Unfortunately, such data is practically non-existant on the article level beyond our OpenArabicPE corpus. The situation is only marginally better on the issue level. Available metadata is not commonly provided in a standard-compliant and machine-actionable format. But even then, the vast majority of articles would remain outside our analytical scopes. Many publishers did not provide (meaningful) bylines and the majority articles in journals and newspapers from Beirut, Cairo or Damascus did not credit their authors (c.f. Table). One promising approach is to subject all articles in our corpus to stylometric analysis—a method that computes degrees of similarity by comparing lists of most frequent words.

| al-Muqtabas | al-Ḥaqāʾiq | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| token | total | author | total | author |

| volumes | 9 | 3 | ||

| issues | 96 | 36 | ||

| pages | c.7,000 | 1,446 | ||

| articles (total) | 2,737 | 323 | 360 | 76 |

| articles (independent) | 717 | 284 | ||

| words | 1,953,952 | 625,333 | 300,186 | 40,868 |

Table: Basic publication statistics for al-Muqtabas and al-Ḥaqāʾiq

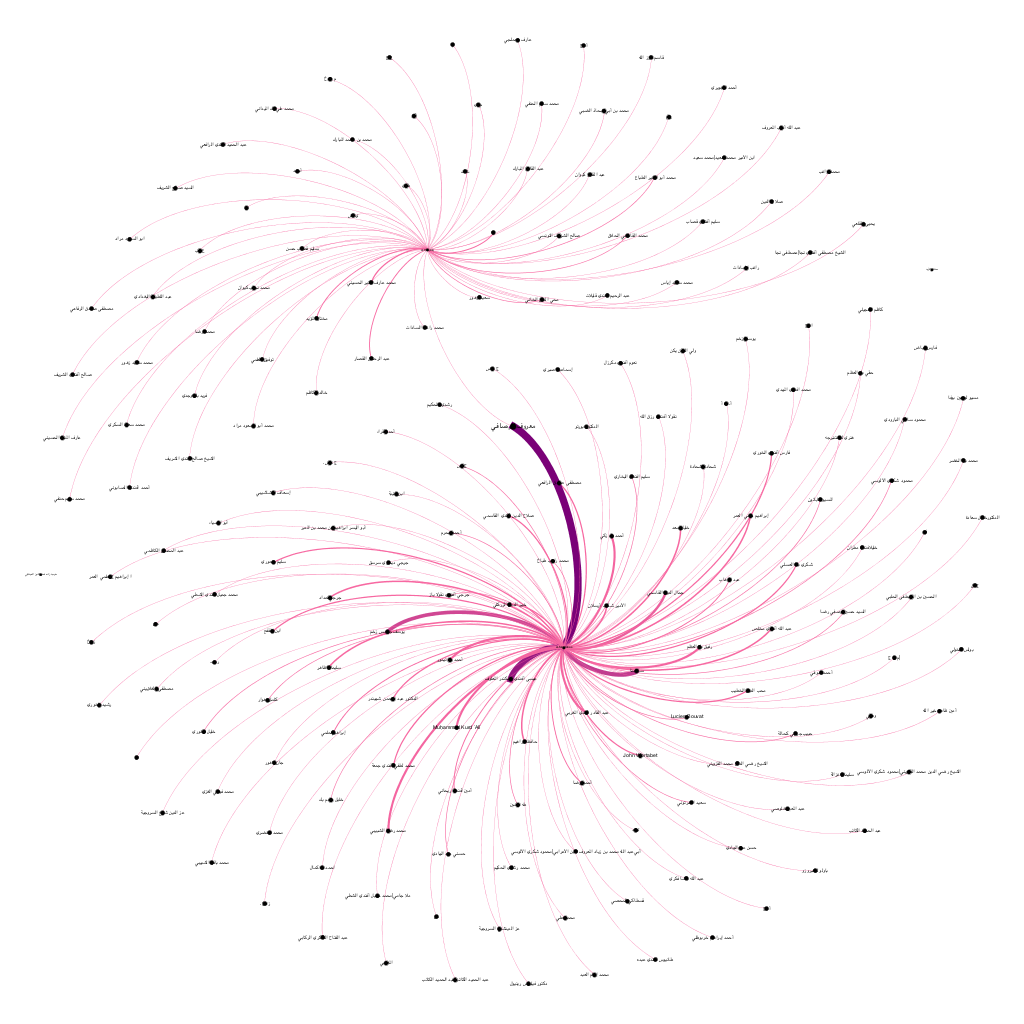

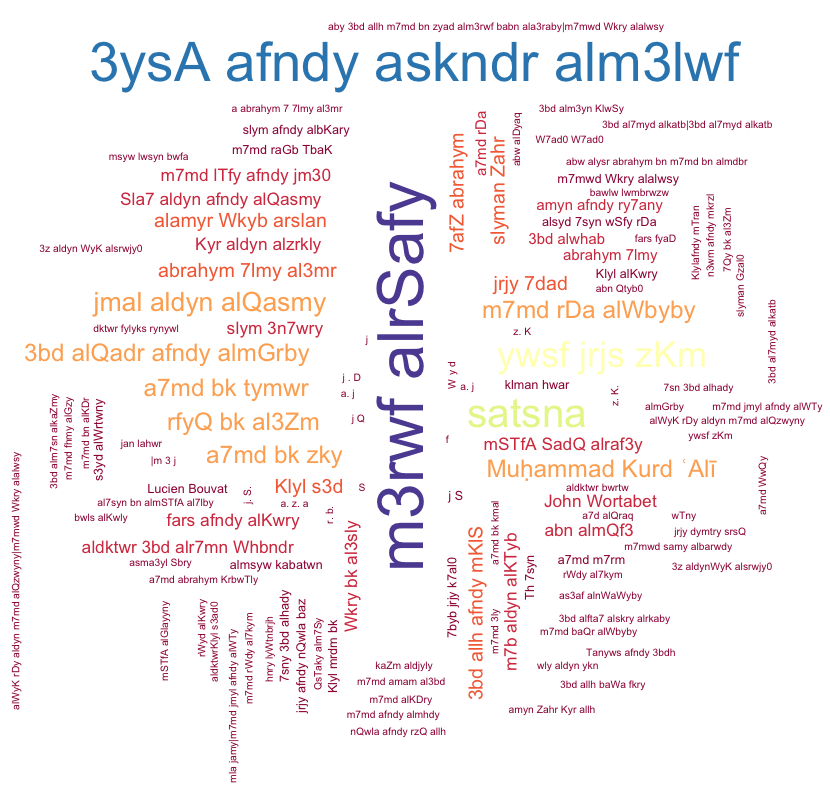

We can currently identify only 126 named authors for al-Muqtabas and less than 60 for al-Haqāʾiq. Quite a significant number appear only with their initials, particularly in al-Ḥaqāʾiq, and all of them were men. Only 50 authors published more than one article in al-Muqtabas (Fig. 1 and 2).

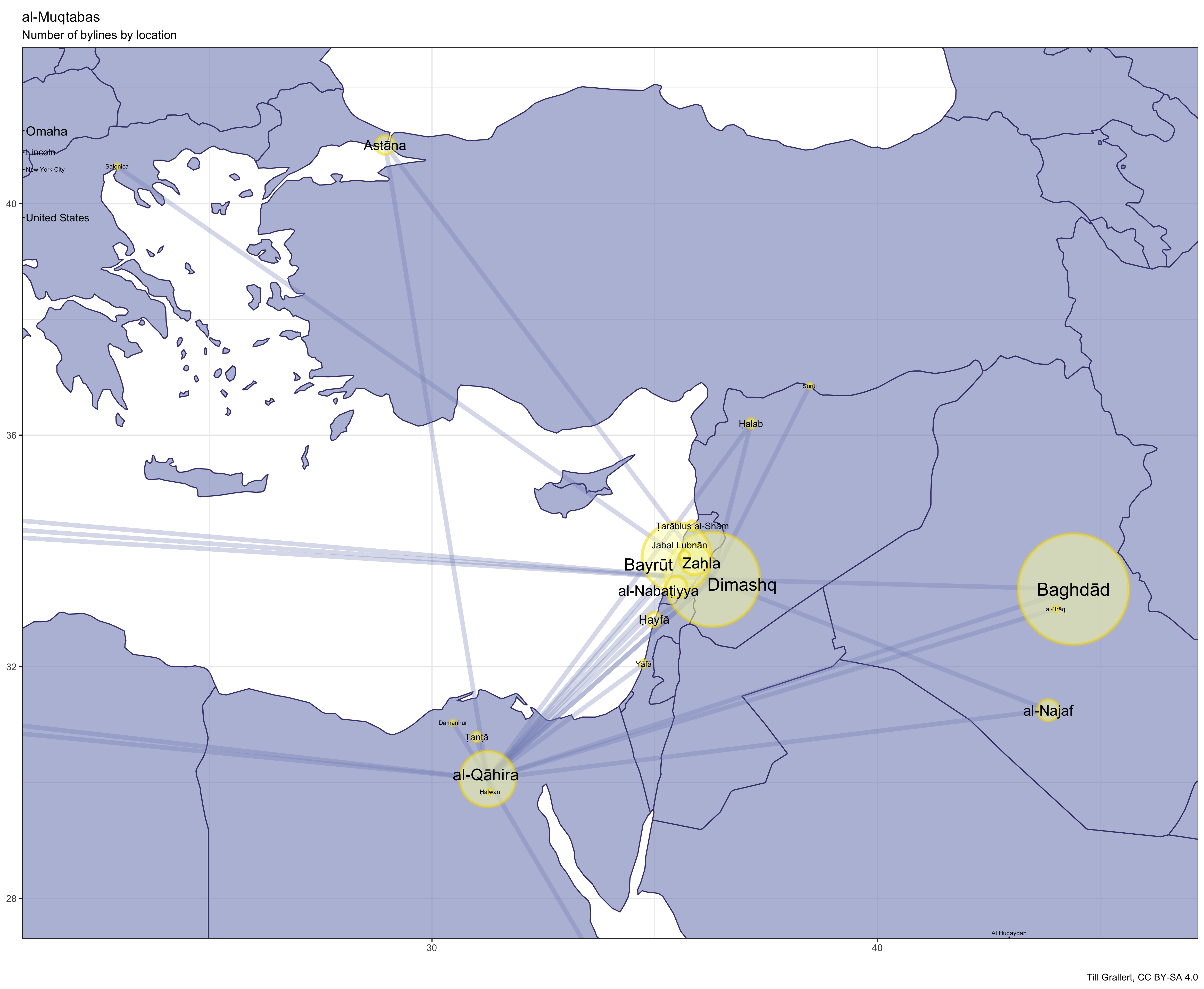

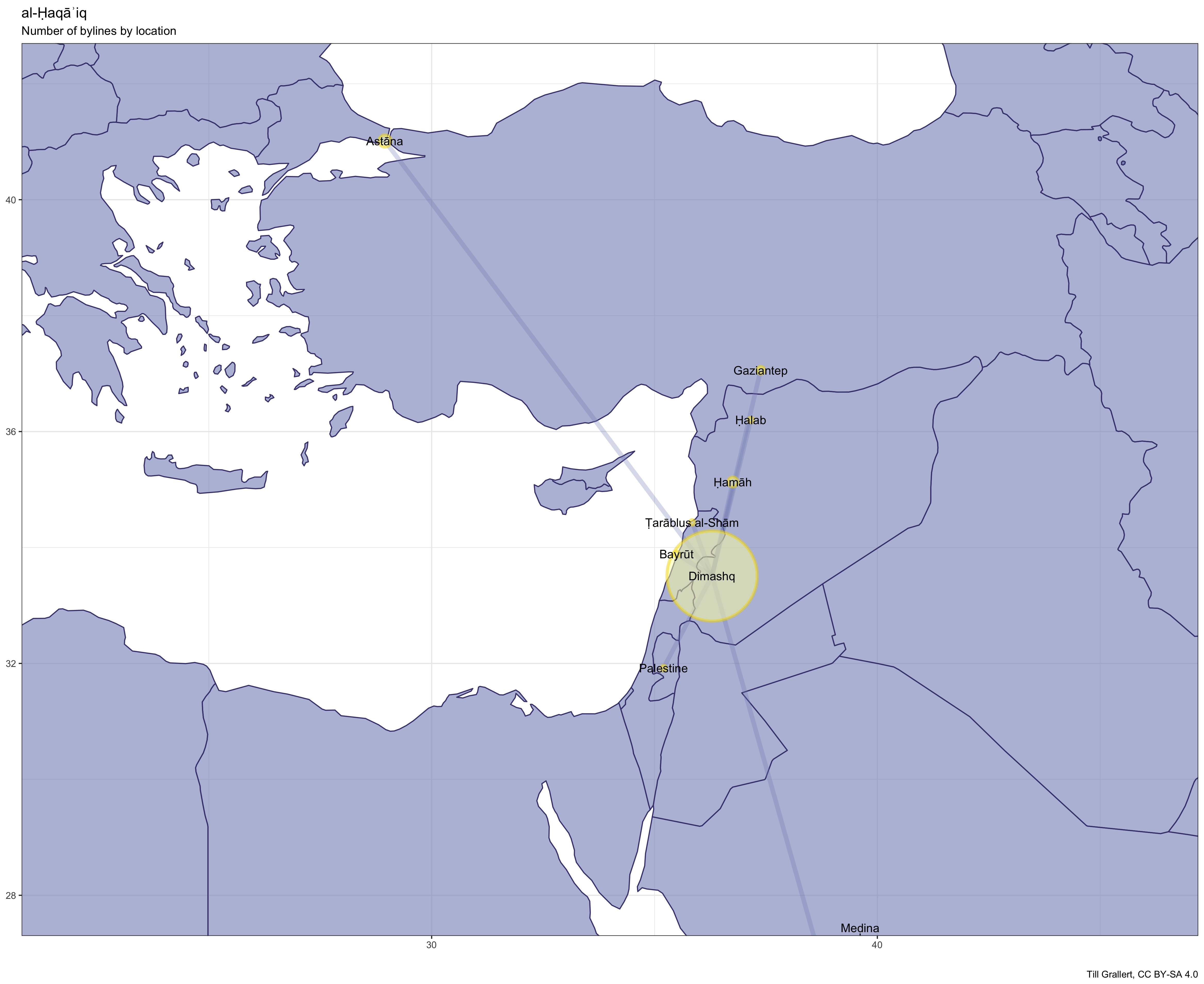

The geographies of these networks, as recorded in the bylines, are telling (Fig. 3 and 4): al-Ḥaqāʾiq’s network was mainly restricted to the inland cities of Greater Syria (Bilād al-Shām) while al-Muqtabas reached well beyond to Egypt, Iraq and even America, turning the proverb “Cairo writes, Beirut publishes and Baghdad reads” upside down with Baghdad well ahead of even Damascus.

Two of the four most prolific authors in al-Muqtabas, with more than ten bylines to their names, wrote from Baghdad: Maʿrūf al-Ruṣāfī (24 articles) and Buṭrus bin Jibrāʾīl Yūsuf ʿAwwād, using at the pen name Sātisnā (14). ʿĪsā Iskandar al-Maʿlūf (20) filed his articles from across Mt. Lebanon and Yūsuf Jirjis Zakham (13) from Omaha and Lincoln, Nebraska, USA. Only the fifth most prolific author was a native resident of Damascus: Jamāl al-Dīn al-Qāsimī (8). The four men out of the five, for which we can find biographical records, are in many aspects exemplary of the modernising late Ottoman Empire and the Middle East: Coming from a plurality of religious and social backgrounds—Greek Orthodox, Catholic and Sunnī Muslim, priest and leading Salafi thinker of the second generation, part-time officials, of simple means and members of the old elites—they belonged to the same generation (born between the mid-1860s and mid-1870s), were highly mobile and well-travelled and had good command of local as well as foreign languages.

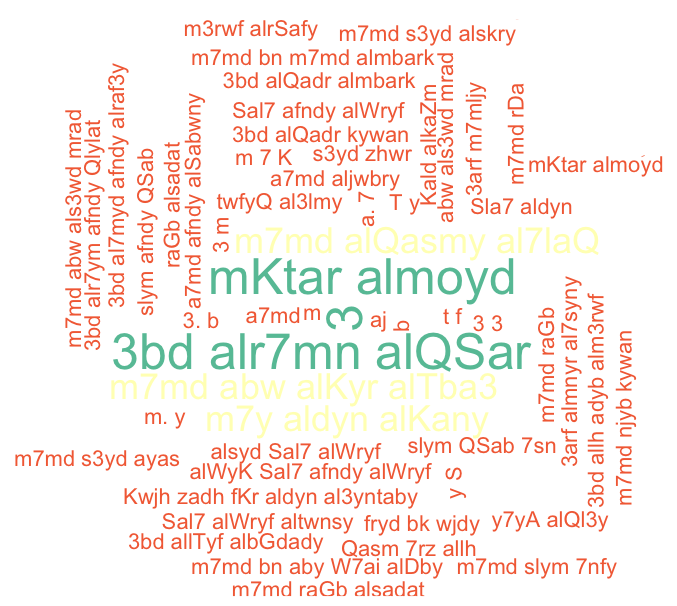

The picture is different for al-Ḥaqāʾiq, which was repeatedly in conflict with al-Muqtabas over the latter’s supposed moral laxity. Its most prolific contributors were Damascene Sunni religious scholars from notable families, many of whom were at least one generation older than its opponents, among them Ibrāhīm Mardam Bek, Muḥammad ʿĀrif al-Munīr al-Ḥusaynī (b.1847/48), Mukhtār al-Muʾayyad (b.1822) and Muḥammad al-Qāsimī (b.1843), whose son Jamāl al-Dīn al-Qāsimī was among al-Muqtabas’ contributors. Against this backdrop the initially surprising finding of practically no overlap between the two networks of authors published in journals from the same city, becomes less so (Fig. 5).